5

July, 2018

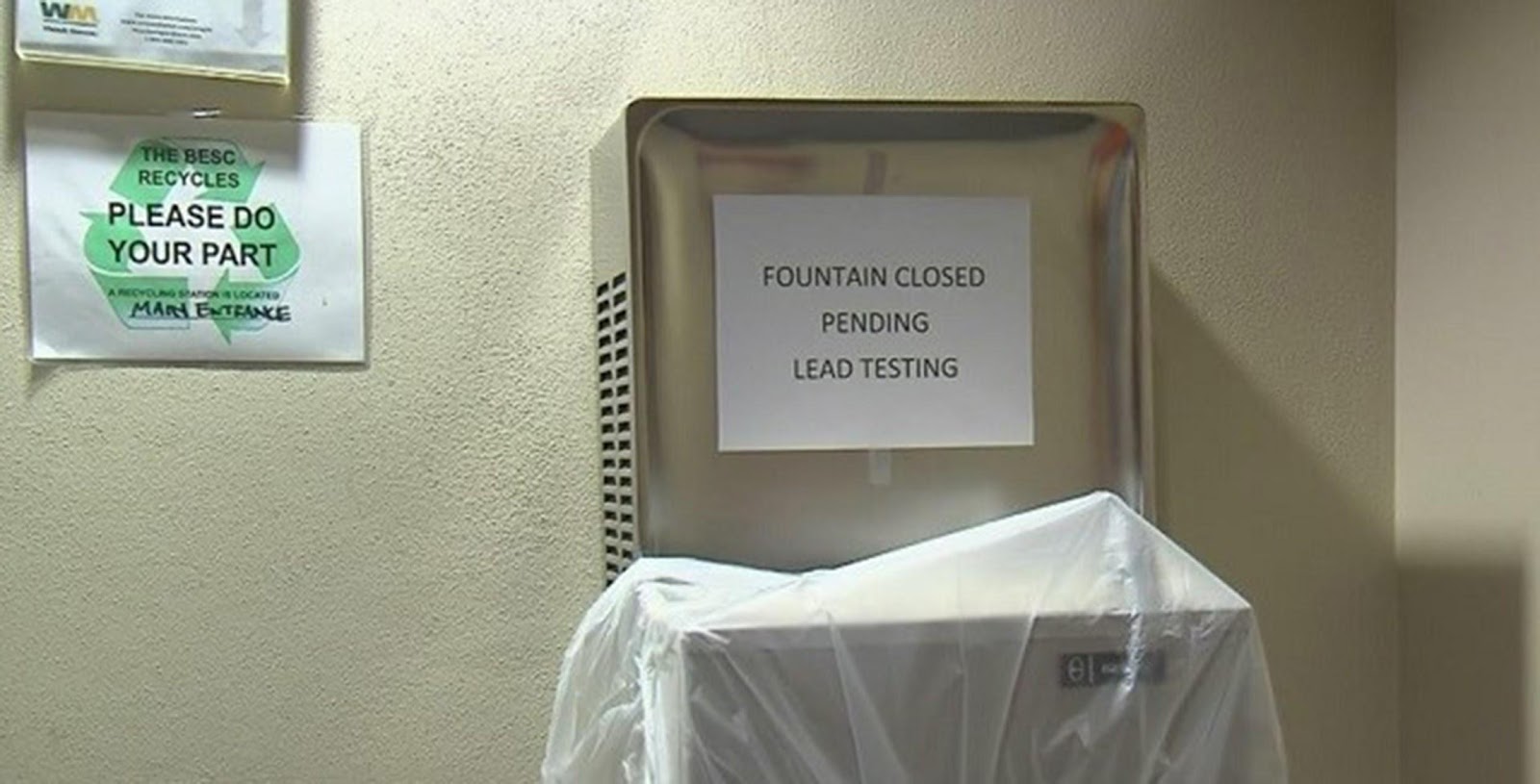

In the wake of the crisis in Flint, Michigan, schools across the United States are testing their drinking water. Because of major national gaps in water infrastructure funding and regulations, many are unfortunately finding high lead levels.

They raise the question, “How much lead is there in our schools’ water?”

How severe is the problem of lead in school drinking water?

Lead in school drinking water is a serious issue across the country. Lead levels above US EPA standards have been found in schools from Portland, Oregon to Washington, DC. Already in 2017, news of lead in public school drinking water has come from New York City and throughout Arizona.

It is sadly no surprise that lead contamination is often found in poorer cities and towns, such as Flint, Michigan or Newark, New Jersey. In Newark, about one quarter of school samples contained lead in 2016. Some of those taps have shown lead levels above EPA standards since 2011.

However, that isn’t to say that lead contamination is only limited to poorer areas. Across the state of Massachusetts, a 2016 statewide testing program revealed 164 public schools had elevated lead levels, out of the about 300 tested.

The news in Massachusetts has caused surprise and concern. Glenn Koocher, Executive Director of the Massachusetts Association of School Committees, expressed his alarm. “The presence of lead in any school water supply is distressing. This report should be a call to action.” He recognized the systemic nature of the problem, noting, “The real challenge for us is to prioritize the replacement of lead water pipes as part of our national effort to improve our infrastructure.”

Results to date may only be the tip of the iceberg. Richard Maas, former Co-director of the Environmental Quality Institute at the University of North Carolina-Asheville, estimated that if samples were taken at every school tap in the U.S., 10-20% would test positive for lead. Some schools have even uncovered levels as high as those found in Flint homes. Evidence indicates a pervasive problem, but due to gaps in testing, there’s no way of verifying the problem completely.

What are the health dangers of consuming lead in drinking water?

Lead directly affects children at school by impairing learning and cognition. Lead is correlated with lower standardized test and IQ scores in children. Even after “safe” levels of exposure, its effects are profound.

Lead is a toxin that can affect almost every organ in the body. In children, lead poisoning may negatively impact learning, motor skills, and hormones during crucial years. It can cause developmental delays (for example, delays in speech or puberty), lower IQs, decreased hearing and balance, irritability, loss of appetite, weight loss, sluggishness and fatigue, abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation, seizures, and consumption of items that aren’t food (pica).

Though the EPA only requires action if lead levels in water reach 15 parts per billion, no level of lead is safe to consume. This is especially true for children, whose bodies absorb and accumulate lead more easily than adults.

Lead directly affects children at school by impairing learning and cognition.

Are schools at a higher risk than other places of lead in drinking water?

Most schools are at higher risk for lead in their water than other types of buildings, such as homes (though lead is a problem in many homes as well). There are three reasons for this:

First, most school buildings are decades old and likely to have some lead in their plumbing. In 2013, school buildings in the US were 44 years old on average. By contrast, schools are not considered “lead-free” by today’s standards unless they were built in 2014 or later. Instead, their plumbing materials may contain up to 8% lead.

Second, schools are used primarily in the daytime and during certain times of the year. Water stays in pipes overnight and during several weeks, even months, in the year. As water sits in pipes and plumbing containing lead, lead accumulates in the water, causing high concentrations of lead to materialize.

Third, there is no lead testing rule specific to schools despite their higher risk, so schools may be tested infrequently or sporadically from varying taps.

Lead is particularly dangerous in schools because of the serious effects it can cause for children. Children absorb lead more easily than adults and experience the most severe, long-term effects of lead poisoning.

Aren’t there laws that prevent lead in drinking water?

Yes, but they do not guarantee that there is no lead in school water. The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requires utilities to test only some taps in each water system, which can include schools but doesn’t cite them directly.

There is no federal law specifically requiring testing of drinking water in schools that receive water from public water systems. This means that about 90% of schools may be used as a sampling location (i.e., tap) for a public water system’s lead testing required under SDWA, but there are no federal requirements for more extensive testing. Schools that do have their own water supplies are subject to more thorough regulation and sampling.

States and towns/cities may also establish their own programs for testing drinking water lead levels in schools. Several, including Illinois and New Jersey, have implemented statewide testing since the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. In Seattle, all schools must be tested every three years. School districts, such as Newton Public Schools in Massachusetts, discovered lead as a result of their own testing programs.

Massachusetts is one state that must improve its testing standards. Each public water system must include samples from at least two schools or early education care centers per district in their testing. Depending on system water quality, these samples may be taken as infrequently as every three years. There can be several sampling periods between tests at each school. This has allowed lead to enter schools’ water unnoticed, as evidenced by the state’s 2016 testing assistance program.

Who is at highest risk from lead in drinking water?

What are the steps to test for lead in water? How difficult is it?

There are several options for testing lead content in school drinking water. If you are concerned about the possibility of lead at your school, take action by learning the options for testing. Find more resources on our website at becausewater.org.

How can schools take steps toward safe water if they discover lead?

There are two recommended solutions to remediate lead from schools water.

First is traditional pipe remediation, which actually requires identifying the source of lead, which can come from the service line, internal piping, or fixtures. While this could remove all lead from the water, the process can be extremely expensive and time-consuming.

A growing alternative for schools is to install a filtration system that will reduce lead to safe levels. Assure that the filter is safe by looking for independent certification by NSF & WQA.

What resources are there for schools concerned about lead in drinking water?

- US EPA’s 3T’s for Reducing Lead in Drinking Water: Testing.

- EPA Safe Drinking Water Hotline: 1-800-426-4791.

- How to Remove Lead from School Drinking Water.

Lead contamination of school drinking water has been a neglected issue across the country. There are some regulations and programs that monitor lead in school water, but these are largely insufficient. Therefore, ultimately each school (and you, reading this article) is responsible for making sure that each school’s drinking water is safe.

Sources

US EPA. “Basic Information About Lead in Drinking Water.”

Mayo Clinic. “Lead Poisoning Symptoms and Causes.”

US EPA. “Drinking Water Requirements for States and Public Water Systems: Lead and Copper Rule.”

US EPA. “Consumer Confidence Reports (CCR).”

Huffington Post, June 2016. “Portland, Oregon Has A Lead Problem. Kids Are Paying The Price.”

The New York Times, March 2016. “High Lead Levels Found at More Newark Schools.”

Boston Globe, June 2016. “High Lead Levels Found More Than 160 School Buildings in Mass.”

The Washington Post, March 2004. “EPA Asks for States’ Plans on Lead.”

The Guardian, March 2016. “Alarm over lead found in drinking water at US schools.”

WebMD, 2001. “‘Acceptable’ Lead Levels Linked to Lower IQ Scores in Kids.”